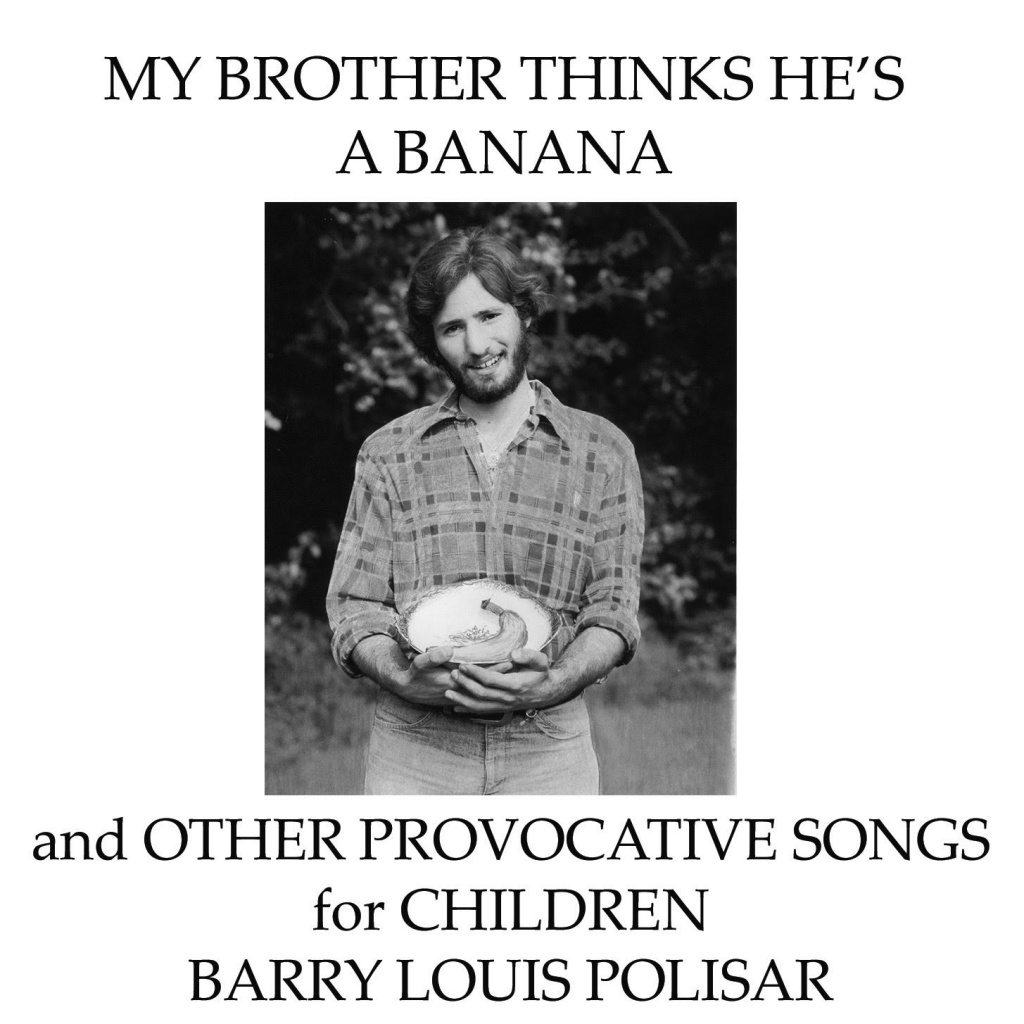

My Brother Thinks He’s a Banana

and Other Provocative Songs for Children“Barry Louis Polisar is a pioneer in children’s music.”

– The Providence Journal, Providence, Rhode Island

“He Playfully explores the childhood experience.”

– American Teacher Magazine

“Listen to your kids. They’ll explain the jokes to you.”

– The Virginia Pilot, Virginia Beach, Virginia

Barry’s second recording was released in 1977 and he joked that he only used three guitar chords on the whole album because he only knew four chords and didn’t want to show off. Who knew it would sell so well and help launch Barry’s career. One listener wrote, “Wicked joy…you are a Shel Silverstein with hair.”

Rediscovering Barry Louis Polisar

Returning to a forgotten childhood favorite with

a new generation

Review written by Boaz Vilozny

December 1, 2008

When we were kids and our parents took us to the library, for over a year we brought home one record whenever it was available. The album cover featured a skinny, goofy-looking guy cradling a banana in his arms. Looking back, it’s hard to believe our parents put up with hearing the record over and over, but maybe it was the trade-off for keeping me, my older sister, and my eight-year-old brother entertained and out of trouble. The record was Barry Louis Polisar’s My Brother Thinks He’s a Banana and other Provocative Songs for Children.

We’d sing along, laughing knowingly at the vivid descriptions of terrorized baby sitters and happily dysfunctional families. Twenty years later, I could still remember many of the lyrics and the abrasive timbre of the singer’s voice. When I started to look for recordings for my own five-year-old, I half-heartedly looked for that old record, but wasn’t surprised when I couldn’t find it in music stores. That primitive, insurgent sound couldn’t have appealed to a broad, normal audience–it was too raw, too funny, too true.

The only way I expected to hear Polisar’s voice again was in my own living room, maybe after buying an old record online somewhere. And yet, a few weeks ago, twenty years after last hearing My Brother Thinks He’s a Banana, I was sitting in a coffee shop and I heard that voice. It was in the background, under the hiss of the espresso machine, but unmistakable. The song was as familiar to me as one sung in kindergarten, like the ABC’s. The teenage barista didn’t know who was singing, but we were listening to the soundtrack from Juno. A quick Google search showed what I hoped–the song was All I Want Is You, and it is from that very same record that was in constant rotation on our living room hi-fi.

I downloaded the whole album for a mere eight bucks, and it was just as good as I remembered. Some of the songs were even funnier from the perspective of a “grown up” and a parent. Others seemed more edgy–even a little creepy. I convinced a friend to buy the album for his kids, but it was quickly banned in his home. It’s not hard to see why–lyrics written over thirty years ago about taking a little sister to the woods and tying her to a tree don’t sit well with parents. Others, such as My Mommy Drives a Dumptruck, would seem to be in line with modern progressive values, until the song takes a turn for the absolutely ridiculous and, to some, offensive. I find it easier to overlook these slights to parental values when seen as part of the album’s overall tone of complete and unapologetic silliness. Children hear the gender-twisting Mommy Drives a Dumptruck just before I Have a Dog and my Dog’s Name is Cat. For them it’s not progressive or postmodern–it’s just fun and funny. And good.

The simple tunes, carved out with a twelve string guitar and catchy melodies, come straight from the stripped down folk style pioneered by Pete Seeger and hipsterized by Bob Dylan. Those influences are apparent when listening to Polisar’s songs. His lyrics also have much in common with the innocently sinister poetry of Shel Silverstein. The guitar playing is nothing special, but provides the perfect platform for Polisar’s theatrical voice and expressive story-songs. The rhythm of each song is derived from the familiar “chung-chaka-chunk” heard in Johnny Cash’s I Walk the Line, played either fast, medium or slow. And yet, after playing the album for several days straight on my laptop (On my wife’s insistence we burned a CD so our daughter could listen in her room), the songs haven’t grown old or any less hilarious.

Polisar seems to know exactly what kids want: good melodies, simple music, and lyrics they can relate to. To be sure, Ella doesn’t catch every phrase of every song. The brother who thinks he’s a banana, we are told, has read the Bhagadvagita. But those details are overlooked. The unfortunate scenario in My Brother Threw Up on my Stuffed Toy Bunny is instantly recognizable to anyone in a family with children.

Will the classic recordings of Barry Louis Polisar be rediscovered as children’s music for our generation? Not likely. But for those who like their kid’s music raw and unrefined, these songs are a welcome alternative to the sweet, overproduced, unimaginative fare marketed for children. Even Raffi, who is always popular at our house, sounds like a Canadian milk-toast after listening to My Brother Thinks He’s a Banana. And who knows? Maybe one day we’ll trust our kids enough to let them listen to songs that make us a little uncomfortable, which is probably how they feel when we listen to NPR. At the very least, the digitized version of Polisar’s record is a gaunlet thrown down for the twenty-first century. There is no excuse for lame children’s music.

At this time, I suspect the true genius of Barry Louis Polisar may be lost for a few generations. Parents who keep their toddlers on leashes are unlikely to see the educational benefit of the brief existential tune, My Name is Hiram Lipschlitz and my Problem’s Pretty Clear. And the iPod generation, while temporarily infatuated with the sweet and unchallenging All I Want is You, will not likely be making One Day My Best Friend Barbara Turned Into a Frog a staple on their playlist. Perhaps, however, Polisar’s legacy will be heard in other ways. For those of us inoculated in childhood with those irreverent songs, we know kid’s music doesn’t have to be boring, or dumbed down, or even safe. My own post-toddler anthem You’ve Got to Keep that Pee in Your Body has quite a bit of Polisar influence, despite having been written before his rediscovery. The seed was sown long ago, with a scratchy record playing in our suburban townhouse.

At this point, my daughter has half the songs on the album memorized. When I played it for her for the very first time, she sat perfectly quiet beside the laptop with her hands in her lap. After the seventeen songs had finished, the play list instantly queued up the Beatle’s Get Back. Ella sat upright and looked at me. “What is this? I want to hear the funny songs.”