My Back Pages: From Protest to Music

The first time I had my picture in the newspaper, it was on the front page of The Washington Post and had nothing to do with my music or singing career.

In November, 1971 President Nixon announced that the war in Vietnam was winding down. Fewer American soldiers were dying, but President Nixon’s policy of increased bombing of the Vietnamese countryside had actually increased the civilian death rate there.

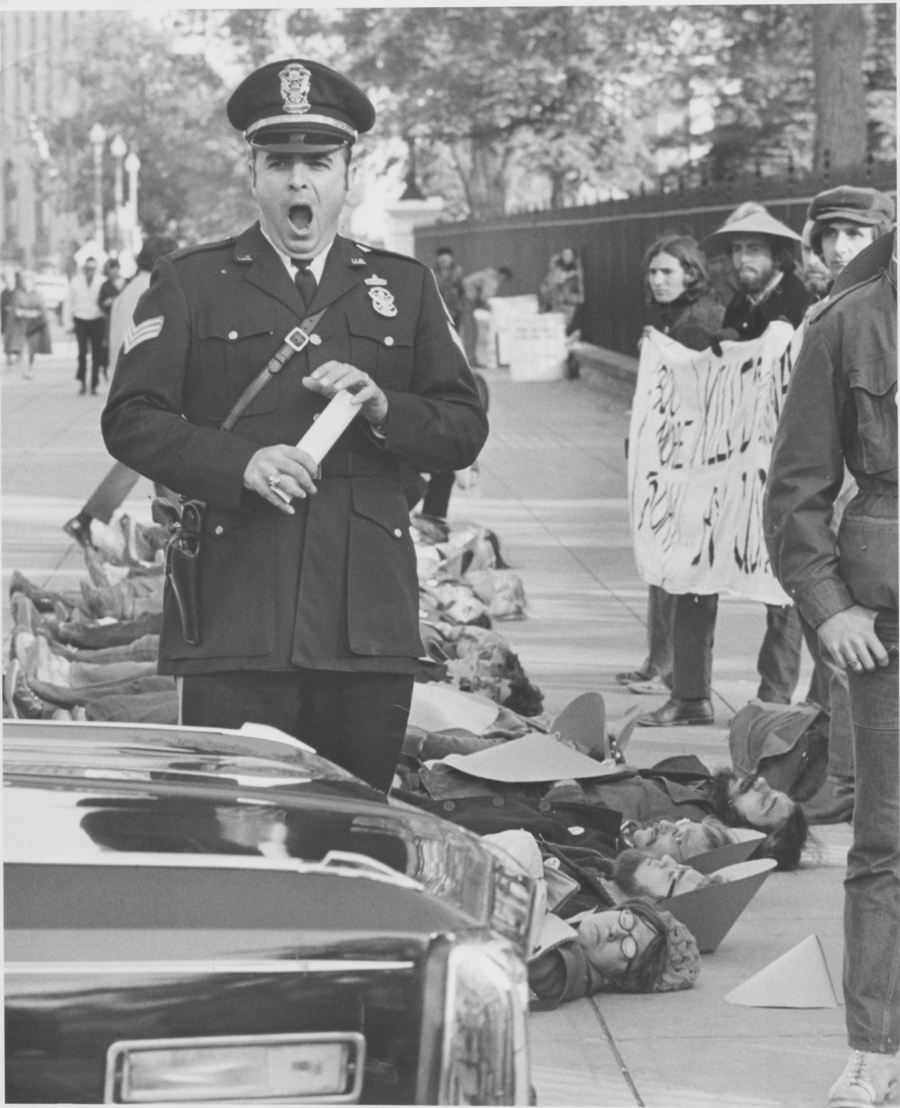

The “300 More Today” protest—meant to highlight the number of civilians killed daily by US bombings—was led by a group of religious leaders concerned about the daily civilian death toll from the bombings. It was a quiet protest deserving only a footnote from that turbulent time, but it went on for a month with daily “die-ins” in front of the White House.

I was just about to turn seventeen years old in November, 1971, but I had been deeply involved in the protest movement. The Washington Post ran a photo of a bored policeman in front of the demonstration, taken by Post photographer Harry Naltchayan. I was on the left side, holding the banner that read “300 More Today.”

The photo went on to win a prize at the White House News Photographers Association and was displayed at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. It was meant to show how ordinary the protest movement had become, but that was the point of the protest; turning away from the death and destruction 10,000 miles away was—to use Hannah Arendt’s phrase—accepting the banality of evil.

I ended up working at the Indochina Resource Center, a clearing house for information on Southeast Asia run by Don Luce and Fred Branfman. Don was the US aid worker who helped expose the Tiger Cages at Con Son Island (where political prisoners were kept) and Fred had written a book exposing the illegal bombing of the Plain of Jars in Laos.

Those were interesting times.

While watching the Vietnam Veterans Against the War stage a protest at a local shopping center, I overheard a man arguing with some protesters about the morality of the Vietnam War. I joined the conversation and long after everyone else had walked away from him, we talked for almost two hours. We didn’t change each other’s minds, but we did have a civil conversation. He gave me his card as we said goodbye: He was John Lofton, from the Republican National Committee. We stayed in touch for a while—and years later, he appeared on The McLaughlin Group, arguing with Frank Zappa about record labeling and censorship in the music industry.

The father of Maryland’s current Governor had been a US Congressman representing my district. I exchanged many letters about the war with him during this time. When I suggested a face-to-face meeting, Congressman Hogan wrote back and said that we knew each other’s views and he saw no reason to meet in person.

I persisted in my requests and he eventually agreed to meet. When I think about that now, I have to give him credit for carving out time for a young constituent who was not even old enough to vote—and clearly would not be one of his supporters; he listened to my position and shared his views with me.

Some may remember that as a Congressman, Rep. Larry Hogan stood alone when he broke ranks with the Republican Party on the House Judiciary Committee, voting for President Nixon’s impeachment.

By then, the war in Vietnam had expanded to Laos and Cambodia.

I used to joke that I knew the guy who was responsible for ending the Vietnam War. His name was Harry and he had held a one-person vigil outside the White House, standing silently with a sign, day after day, protesting the war.

During the Watergate hearings, someone on the White House staff reported that there was this one lone guy who used to stand outside with a protest sign and they reported that this solitary protester drove Richard Nixon crazy—and Nixon wanted him investigated and removed.

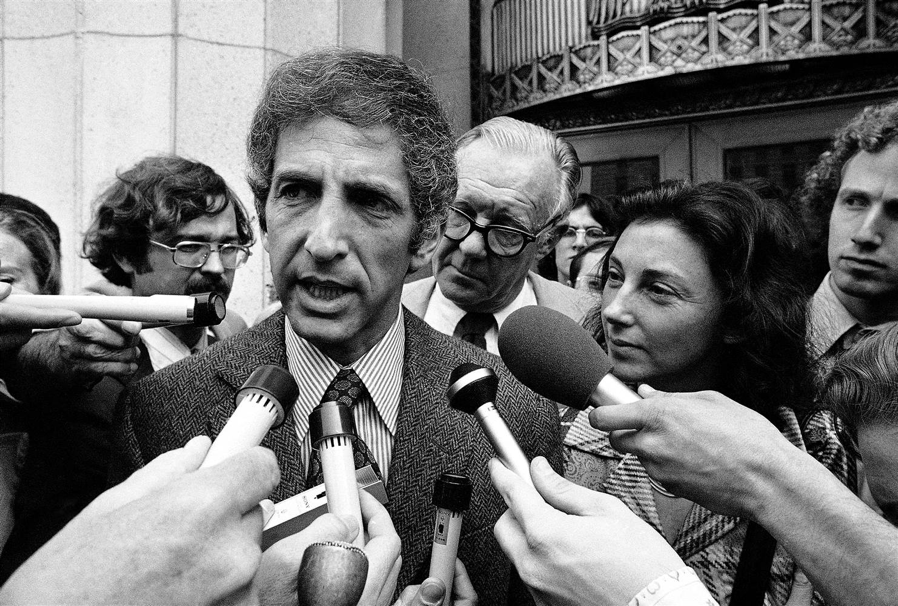

Eventually, they began investigating other people in the protest movement, tapping phones and breaking into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s therapist, looking for information that would discredit him. This culminated with Watergate and thanks to the law of unintended consequences, Watergate helped bring about an end to the war.

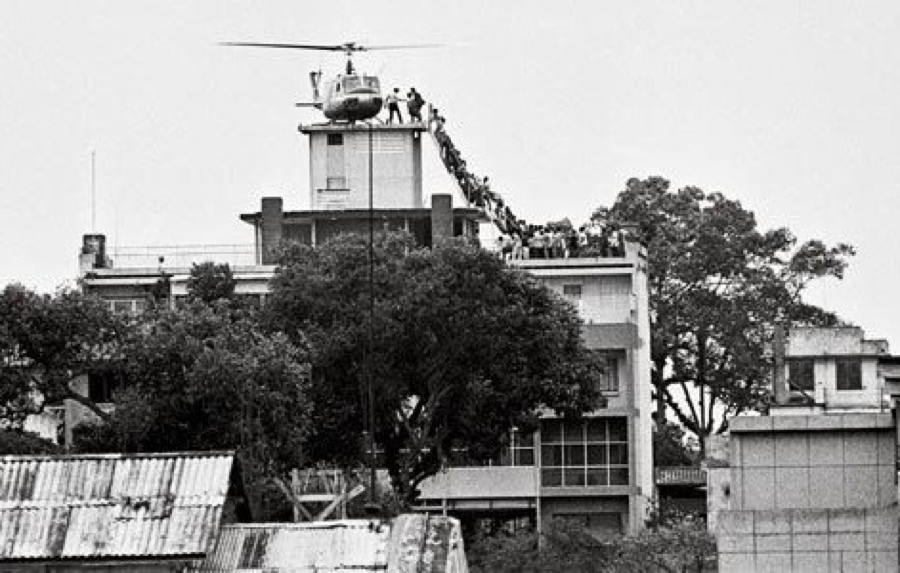

After Watergate, the US Congress cut off funding for further military action in Indochina. Saigon fell, and the war ended—but certainly not the way many in the anti-war movement wanted it to. The anguished scenes of helicopters leaving the American Embassy, abandoning the families of those who had helped the Americans during the war years were broadcast around the world.

As the war was ending, the focus of my life changed.

Just before I started college I bought a $45 nylon strong guitar–and taught myself how to play.

In the Spring of 1975, while at the University of Maryland, a teacher asked if I’d come to her school and perform for her kids. At that very first concert, I heard another teacher yelling at her students and copied down what she said.

I went home and wrote a song called “I’ve Got a Teacher, She’s So Mean.” It was written from a child’s point of view and was clearly influenced by my earlier political life.

Surprisingly, teachers began asking if I could come to their school to sing that song.

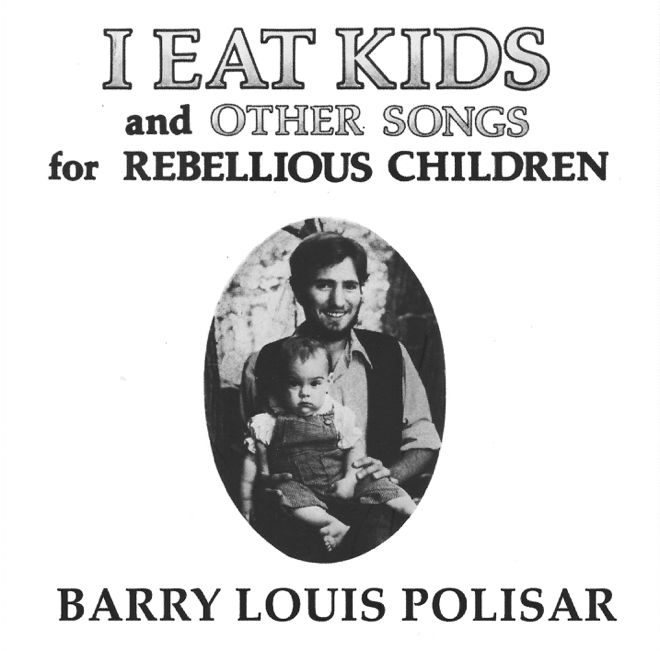

By the summer, I had written enough songs to fill a record, and formed my own “people before profit” record company to send my music out into the world. Many of my early songs gave voice to the concerns of kids who normally didn’t have a way to have their complaints heard. Though I hadn’t been playing guitar for long and couldn’t even tell when my guitar was out of tune, I vowed to record my songs even if some of the songs would be unpopular and cause me trouble.

My first album was called “I Eat Kids and Other Songs for Rebellious Children.”

My music career was a direct descendant of my earlier experiences and many of the songs on those early albums reflected that point of view.

One song on my second album was about someone being chased by a Cyclops only to find that the one-eyed monster was in pursuit of romance. It was called “The Apple of My Eye” and had the line “Then she kissed me on the face and I know that I turned red, but you know what they say: better red than dead.” I was playing on the expression, “I’d rather be dead than red” but hearing me sing that song on TV prompted one listener to denounce me as “Commissar Polisar” suggesting I was preaching communism to young children.

Another listener returned my album and said my songs were “demonic anarchy” and she was adding me to the top of her prayer list.

Despite the concerns, most people understood the humor in my songs and I’m forever grateful for the success I’ve had. In a field where many artists and musicians are not able to support themselves, this has been the only job I’ve ever had for over forty years.

I still work in schools where budgets are often non-existent for things like music and writing programs because, to paraphrase Willy Sutton, “that’s where the kids are.”

But before all that, there was this photo…and this life.

—Barry Louis Polisar, October, 2017

Since 1975, Barry Louis Polisar has traveled throughout the US and Europe, singing and performing in schools, libraries and Art Centers. He has performed at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, The Smithsonian, and The White House. A five-time Parents’ Choice Award Winner, Barry has written songs for Sesame Street and The Weekly Reader, and starred in an Emmy-Award winning Television show for children. He has written and published over a dozen books and his songs have been recorded by musicians throughout the world. He is in the photo above, taken in 1971.