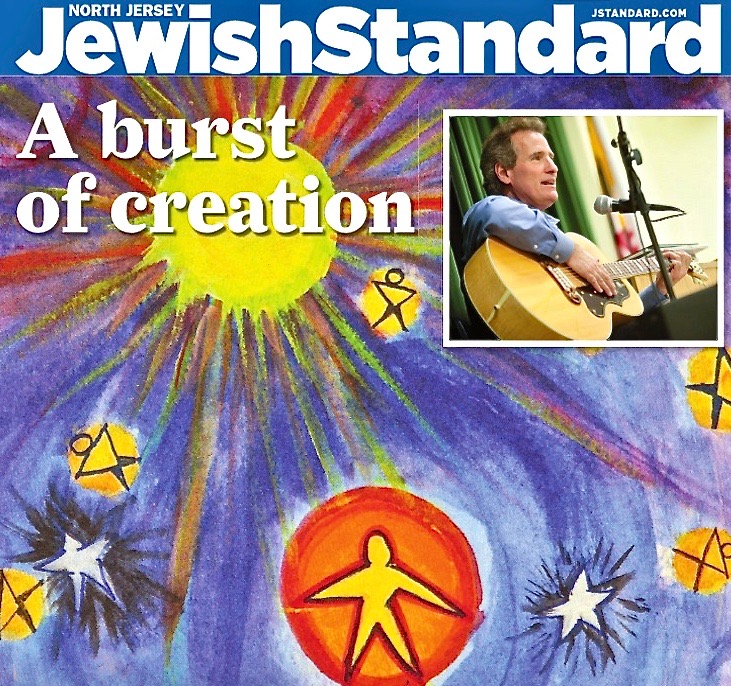

Retelling Genesis: Cover Story in The New Jersey Jewish Standard, Fall, 2014

Okay. Let’s start with full disclosure.

I’ve never met Barry Louis Polisar, so it’s nothing personal. But his music for children was a huge part of our lives, back when my kids and the world and I were young.

Mr. Polisar is based in Maryland, but he sometimes played here; he’d do the occasional early-Sunday-morning live show at WFDU, at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck, and we’d all go to see him. We first heard about him on Kids America, an extraordinary (and therefore short-lived) children’s public radio show aired on WNYC, where such classics as his “I’ve Got A Teacher, She’s So Mean” and “I Lost My Pants” and “Don’t Eat the Food That Is Sitting on Your Plate” were in heavy rotation.

And then, of course, I forgot all about him.

So when word came that he had written a book about Genesis – the first book of the Bible, Beresheit, not the old rock group, I was thrilled. And when I read the book, I was not disappointed.

Mr. Polisar has approached the task with unexpected reverence but also with his usual creativity and verve. The book, “Retelling Genesis,” focuses on the less-prominent characters in well-known stories. Using only the text itself, Mr. Polisar imagines himself into the skins of Esau and Laban, Noah’s wife, Lot’s daughters, and Joseph’s brothers, among others.

Mr. Polisar is a storyteller, and there is a story in the way he found himself writing this book.

He grew up in Brooklyn and then in suburban Washington, D.C., in a Jewish but Jewishly unconnected family, feeling much but knowing little about Judaism.

He has been a children’s performer for 40-some-odd years; his career has been steady, and he’s been in demand during that time – he’s played at the White House, the Smithsonian, and the Kennedy Center, and he’s written songs for Sesame Street. He has also produced a steady stream of children’s books.

Then, in 2007, one of his songs, “All I Want Is You,” was featured in “Juno,” a surprisingly successful movie that both critics and audiences loved. The song is a quintessential Barry Louis Polisar song – the guitar, the harmonica, and the charming lyrics. (“If I was a flower growing wild and free/All I’d want is you to be my sweet honey bee/And if I was a tree growing tall and green/All I’d want is you to shade me and be my leaves.”)

Since then, his name recognition and his popularity have skyrocketed. His music has been featured in movies and commercials around the world.

Since then, his name recognition and his popularity have skyrocketed. His music has been featured in movies and commercials around the world.

He also has become increasingly involved in Jewish life. He published a haggadah a few years ago, and now, here is “Retelling Genesis.”

There is another strand to Mr. Polisar’s life, one to which the lyrics of “All I Want Is You” allude. He is a farmer, a gardener, a finder and fixer of abandoned houses in the country, and a cleaner-up of the land that surrounds them.”

“We” – that’s Mr. Polisar and his wife, Roni, who illustrated “Retelling Genesis,” “bought a farm about four miles north of Silver Spring about 15 years ago,” he said. “It was a 20-acre farm that had been used as a junkyard. It had been on the market for months and months. No one would touch it. I spent a year and a half cleaning the land.” It was a venture in which he found spiritual meaning, as he drew closer and closer to the land underneath the trash.

“My wife has always been an organic gardener,” he continued. It’s not a commercial operation, but we grow our own food.

Next, the couple turned to property that had been in Mr. Polisar’s family since the 1930s. “My grandfather’s parents settled in Colchester, Connecticut, in the 1890s,” he said. “They were part of the big wave of Jewish emigration, part of a group that was settled on farms in New England. My grandfather grew up on a farm, and he told the classic stories about it. He ran six miles to school every day; he had no gloves but he’d carry hot potatoes in his hand to keep warm.

“He went to Yale during the quota system” – which kept all but a few of the most formidably qualified Jews out – “but he had these agrarian roots. My grandmother was more urban, from a shopkeeper’s family, but she was a hopeless romantic who loved living in the country.” So the couple bought 50 acres on the Chesapeake Bay.

The house they built on that land in the 1930s no longer stands. Mr. Polisar’s uncle lived there until he died. He did not make any improvements to the house. He also did not make the killing he could have made by subdividing it and selling it off. “Instead, he kept it the way nature meant it to be.” It was covered with trash, but the trash was only surface deep. Underneath, the earth was protected.

Mr. Polisar’s 88-year-old mother very much wanted the land to stay in the family, so Barry and Roni Polisar undertook another clean-up job. They registered the land in the forest conservation program and promised to keep the land wild and natural. That was a no-brainer for them; they have no interest in anything else.

Next, they bought more land near their own house; again, it had been used as a dump. No one else wanted it. “One day, Roni and I were walking to the ice cream store through a trail in the woods, and we see a sign that says ‘For Sale’ that points to this driveway in the woods. My wife said don’t go look. No more land. So I didn’t look. But then, a few weeks later, the sign was still there.”

Now, cleaned up and de-trashed, the house and land are home to a young couple and some friends, academics who are living out their own 21st-century rural fantasy. “Its the commune down the road,” Mr. Polisar said. “I see these renovations as part and parcel of what I do spiritually and religiously and creatively.”

During all this time, Mr. Polisar had been growing closer to Jewish life. “I had a Tijuana bar mitzvah,” he said. “I had a crash course to learn Hebrew for it, and then I never used it again. In my memory, it was the one and only time my family went to a synagogue. As a 13-year-old, it all felt empty and meaningless. I went through this ritual – but why?”

“When I married Roni,” he said. “The synagogue her parents went to once a year was Orthodox. And they did Passover.

“When I first met her dad, I was an eager student. My memory of those early Passovers was that I would ask questions – I wanted to understand everything – and everyone else was moaning and groaning because it took so long. And then, over time, I noticed that everybody gathered around the table was perplexed by the same thing, and over time I was the one who was starting to answer the questions.”

That’s when he realized that a new Haggadah might be useful. “The ones we used were really confusing, and didn’t provide a context,” he said. “They didn’t explain, for example, that the story was told talmudically. They didn’t have any idea how to read it. The way the stories were presented, people read as if they were reading full sentences. They didn’t understand that they were reading sentence fragments.”

There have been many haggadahs put together to reflect political and social world views, Mr. Polisar said. He wasn’t interested in them either. He wanted the pure text; he just wanted to be able to understand that text. “I wanted it put into traditional and spiritual context,” he said.

“So when we had an opportunity to host a seder, I put together some photocopied pages, culled from various sources, and people took them home and began using them at their own seders.” He ended up publishing the haggadah, called “Telling the Story,” which is now in its third printing, and also posting it online, free, in PDF form. It’s available here.

“So when we had an opportunity to host a seder, I put together some photocopied pages, culled from various sources, and people took them home and began using them at their own seders.” He ended up publishing the haggadah, called “Telling the Story,” which is now in its third printing, and also posting it online, free, in PDF form. It’s available here.

There’s a photo of a bunch of young students using it on iPads and iPhones,” he said. “Just like any other author or songwriter, I know of no greater satisfaction than to be able to write something that really resonates with people.”

And that brings us, at last, to his new book.

“When my kids – 27-year-old twins Sierra and Evan – “were at the synagogue, in preschool and then religious school and then studying to become bar and bat mitzvah, they were required to go to services, I told them that I would never drop them off at the door and leave them. ‘If you go, I am going,’ I told them. So I started going.”

“It was the first time that I had read the Torah as an adult,” Mr. Polisar said. “If you’ve never set foot in a synagogue or church, still you’d know some of the stories, but not all of them. I started reading, and I kept going.

“I’d ask the rabbi, Jonah Layman, a lot of questions, and he was very patient. He was running a Friday morning Torah study class with a bunch of retirees – because who else could be there on a Friday morning? So soon it was me and all those retirees. And I was really lucky, because they had just started Genesis.

“Now, 13 years later, we’re on Leviticus,” he added. It is traditional text study, featuring close analysis and avid tangent-hunting. It appealed to Mr. Polisar’s natural inclination to question absolutely everything – a quality highly prized in such study sessions.

“At the same time, my daughter, Sierra, was in a class where she was asked to write a one-page paper about some well-known story that everyone knows, but to write it from a different point of view. She chose to write about Noah’s wife, and she shared it with me.”

He was so taken with it, he said, that he asked her if he could make some changes to it and use it himself. “She said, ‘Sure. I’ve already turned it in. Knock yourself out, Dad.'”

He did.

At the same time, he said, he had been influenced by “a favorite poet, A. D. Hope, an Australian who had been a contemporary of Auden’s.” (That’s the 20th-century English poet W.H. Auden.) “One of Hope’s books is called ‘A Book of Answers,’ in which he answers famous poems.

“I had wanted to do an album answering famous children’s songs.” He didn’t -he realized that there were not enough famous children’s songs that could be answered or rebutted – but the idea stayed with him, combined with his daughter’s work and his own Torah study, and turned into something else. His new book.

“I wrote the first draft that night, and I have been sitting on it for a dozen years,” he said. “I was questioning who am I to write this book. And every time I went back and read the stories, I got different insights.”

He worked with different translations, but he chose not to include any midrashim – the traditional stories, filtered through different rabbinic points of view, historic eras, and circumstances, that explain or deepen or spin biblical stories. Instead, “I simply wanted to give voice to the characters who didn’t have much voice,” he said.

The effect is a kind of Rosencrantz and Gildenstern-ization of the Torah text.

“I am irreverent in my children’s songs, but I am not here,” Mr. Polisar said. “People have asked if this isn’t an edgy book, but I think that everyone who is engaged in Torah study will find it to be entirely reverential. My heart and soul are in it.

“It might not be a traditional approach to Torah study,” he conceded. But reverence, perhaps, is hard to define, as is relevance.

“I came away from the project with an even stronger respect for the Bible, and for the book of Genesis,” Mr. Polisar said. “It has weight, and it has incredible stories and lessons to tell.”

This story has been edited and abridged from a story written by Joanne Palmer, originally published October, 2014 in The New Jersey Jewish Journal. For additional information and reviews click here.